As North Korea, Iran and China support Russia’s war, is a ‘new axis’ emerging?

The thousands of North Korean troops US intelligence says arrived in Russia for training this month have sparked concern they will be deployed to bolster Moscow’s battlefront in Ukraine.

They’ve also turned up alarm from the United States and its allies that growing coordination between anti-West countries is creating a much broader, urgent security threat – one where partnerships of convenience are evolving into more outright military ties.

Hundreds of Iranian drones have also been part of Moscow’s onslaught on Ukraine, and last month the US said Tehran had sent the warring country short-range ballistic missiles as well.

China, meanwhile, has been accused of powering Russia’s war machine with substantial amounts of “dual use” goods like microelectronics and machine tools, which can be used to make weapons. Last week, the US for the first time penalized two Chinese firms for supplying complete weapons systems. All three countries have denied they are providing such support.

Taking stock of the emerging cooperation, a Congress-backed group that evaluates US defense strategy dubbed Russia, China, Iran and North Korea this summer an “axis of growing malign partnerships.”

The fear is that a shared animosity toward the US is increasingly driving these countries to work together – amplifying the threat that any one of them alone poses to Washington or its allies, not just in one region but perhaps in multiple parts of the world at the same time.

“If (North Korea) is a co-belligerent, their intention is to participate in this war on Russia’s behalf, that is a very, very serious issue, and it will have impacts not only on in Europe — it will also impact things in the Indo Pacific as well,” US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said Wednesday in the first US confirmation of North Korean troops in Russia.

‘Driven by survival strategy’

Decades after the Axis powers of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Imperial Japan and the strident anti-West coalition of the Cold War era – and years since George W. Bush’s dubbed US enemies Iran, Iraq and North Korea an “axis of evil” – there’s a perception that a new, dangerous alignment is on the rise, with Putin’s war as its catalyst.

Such an alignment would bring together two long-time nuclear-armed powers, a state believed to have assembled a host of illegal nuclear warheads in North Korea, and Iran, which the US says could likely assembly such a weapon in a matter of weeks.

North Korea’s military partnership with Russia now links the grinding, hot conflict in Europe to an especially tense period in the cold conflict on the Korean Peninsula, as North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has elevated his threats toward the South, with which it remains technically at war.

Following the intelligence on the North Korean deployment to Russia, South Korea said it could consider supplying weapons to Ukraine, where the US ally has yet to directly provide arms.

For North Korea, where leader Kim has called to ramp up his country’s illicit nuclear weapons program, there’s been little to lose in sending what’s believed to be millions of rounds of artillery, short-range ballistic missiles and, more recently, troops to Russia.

In exchange, cash-strapped and internationally isolated Pyongyang has likely received food and other necessities – and potentially support developing its space capacities, which could also help its sanctioned missile program.

The importance of drone warfare in Ukraine has also seen Russia look to Iran for procurement – deepening a security alignment that dates to 2015 and the war in Syria, when both backed the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

And for Tehran – weighted by hefty Western sanctions and embroiled in the expanding Middle Eastern conflict with US-backed Israel – supplying Russia weapons is thought to potentially boost its defense sector, while its ties with Beijing and Moscow provide it with diplomatic cover.

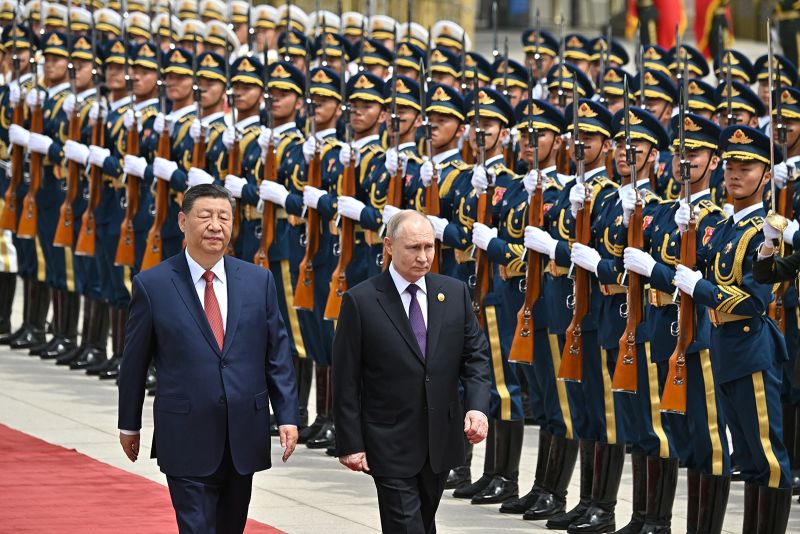

Chinese leader Xi Jinping, who declared a “no limits” partnership with Putin weeks before his invasion, has claimed neutrality in the conflict and has largely steered Chinese firms away from supplying direct lethal aid.

Yet it has filled wide gaps in Russian demand of other goods, including products deemed by the US and others to be dual use, and benefited from Russia’s discounted energy. Beijing defends its “normal trade” with Russia. China has also continued to expand joint military drills and diplomatic ties with a country it sees a key partner in pushing back against the West in international fora.

But even as these four countries have their own motivations to cooperate with one another individually, especially within the context of Russia’s war, clear limits exist in any broader coordination, mutual trust, and even interest in working together – at least for now, observers say.

“This is a set of bilateral relationships driven by each country’s survival strategy, or what’s on the menu for geopolitics and what’s the crisis of the day or the decade that they are dealing with,” said Alex Gabuev, director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin.

“These are authoritative regimes … and they all see the US as a common adversary. That’s the glue that keeps them together, but whether we can talk about a degree of coordination (between all four) … I think we are very far from that,” he said.

That makes the pressing question whether these current alignments can endure beyond the war in Ukraine and evolve into outright coordination between all four nations.

The China factor

A key factor in how any further alignment develops is China, observers say – by far the most powerful player in the grouping, the lead trade partner for Russia, North Korea and Iran, and the nation viewed by the US as its primary adversary.

As its divisions with Washington have deepened, Beijing has ramped up efforts to challenge US global leadership and shape an international order into one that favors China and other autocracies.

Russia’s role in that effort was on show this week in its southwestern city of Kazan, where Xi and Putin hailed their commitment to building a “fairer” world on the sidelines of a summit of the BRICS group whose membership they’d jointly worked to grow this year.

The two have brought Iran into that diplomatic fold and also largely sided with Tehran in the conflict in the Middle East, where its proxies are fighting Israel. China, Russia and Iran have also held four joint naval drills since 2019, and China is by far Iran’s largest energy buyer.

At the same time, heavily sanctioned Iran is no longer the “favorite state for China’s Middle East policy” as Beijing builds relations with wealthier Gulf countries, according to Jean-Loup Samaan, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute.

Beijing also carefully manages its relationship with North Korea – which is almost wholly economically and diplomatically dependent on China. Chinese leaders are widely seen as being wary of the burgeoning Kim-Putin alignment and the potential for an empowered North Korea to cause trouble and draw more US focus to the region.

When asked about the movement of North Korean troops into Russia at a regular press briefing Thursday, China’s foreign ministry said it “does not have information on that.”

While it practices its own aggressive behavior in the South China Sea and toward Taiwan, the democratic island Beijing claims, China may not want to appear to lean too hard into these partnerships and hinder efforts to portray itself as a responsible, global leader.

“Russia, North Korea, Iran is the type of grouping that China least wants to openly associate itself with,” said Tong Zhao, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

China has been “desperate to clarify that it is not a trilateral alliance with Russia and North Korea,” and it also “has more options than these countries … and prefers working with larger number of countries” to compete with the West, he said.

‘A real risk’

Viewed from the West, however, China’s refusal to cut off economic lifelines to a UN sanctions-defiant North Korea and a Russia that has threatened the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine is often seen as an open endorsement of these regimes.

In July, the Commission on the National Defense Strategy, an independent group tasked by Congress with evaluating US defense strategy, said China and Russia’s partnership had “deepened and broadened” to include a military and economic partnership with Iran and North Korea.

“This new alignment of nations opposed to US interests creates a real risk, if not likelihood, that conflict anywhere could become a multi-theater or global war,” it said.

China has repeatedly insisted that its relationship with Russia is one of “non-alliance, non-confrontation and not targeting any third party.”

NATO has also in recent years moved to ramp up relations with US allies and partners in the Asia-Pacific, with a meeting of defense ministers last week joined for the first time by Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

In the short term, Russia’s weapons partnerships also open the door for Iran and North Korea to potentially obtain and produce Moscow’s sensitive weapons technologies and even ship them around the world, according to Carnegie’s Zhao.

The current dynamics also raise the risk that future conflicts – including one where China is at the center and not Russia – see coordination between the four, some analysts assess.

For example, in a potential conflict in the South China Sea or over Taiwan, there is debate over whether Beijing would want to see North Korea or Russia play a role in creating a distraction in North Asia.

But some experts also warn against seeing this “axis” or such a future as a foregone conclusion – as these relationships remain opportunistic, rather than based on deep ideological alignment or trust.

For one, it’s possible that “some more moderate behavior” could be incentivized on the part of China, which could dial down this potential, according to Sydney Seiler, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

But as the optics stand today – “the risk is sufficiently present” that the US could face a future conflagration involves multiple of these countries, he said.